At some point in life, you’ve probably experienced the dread of realizing that you won’t be able to complete a project or assignment on time. But have you ever been so desperate that you’d consider selling your soul to get it done? Well, hopefully not, but you may be interested to know that this is scarily appropriate for this week’s topic: the Codex Gigas.

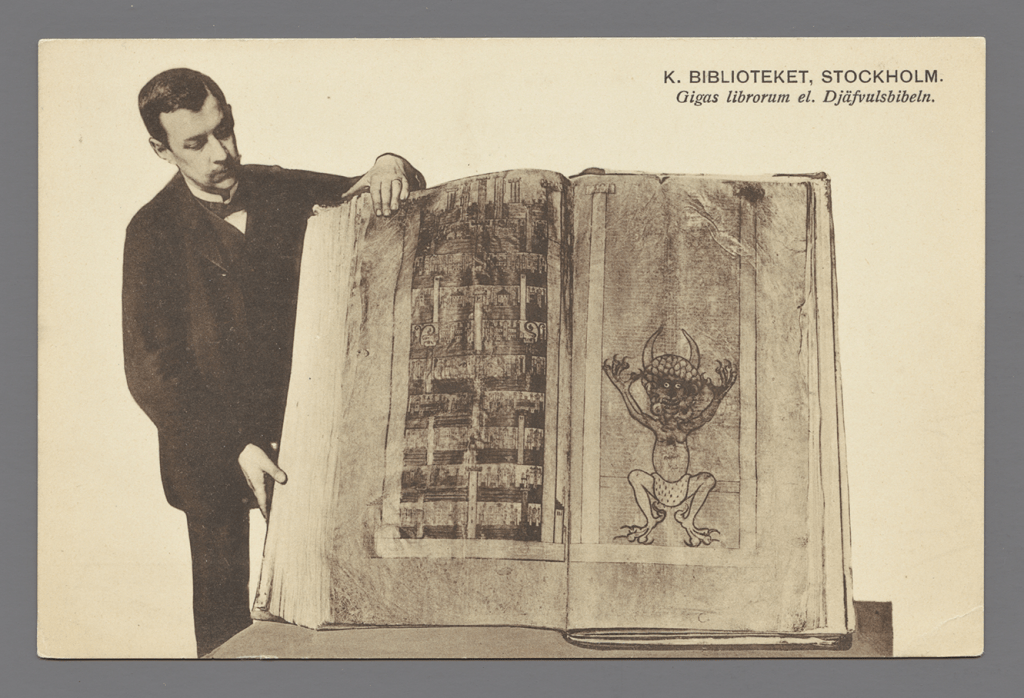

The Codex Gigas, which is commonly known by its cryptic nickname, the “Devil’s Bible,” was written in the early 1200s in Bohemia, where the Czech Republic sits today. In terms of its historical significance, it is said to be the largest preserved medieval manuscript. The book itself is 9 inches (22 cm) thick, 20 inches (50 cm) wide, and a whopping 3 feet (92 cm) tall. It might come as no surprise that the book’s name, Codex Gigas, translates to “Giant Book.”

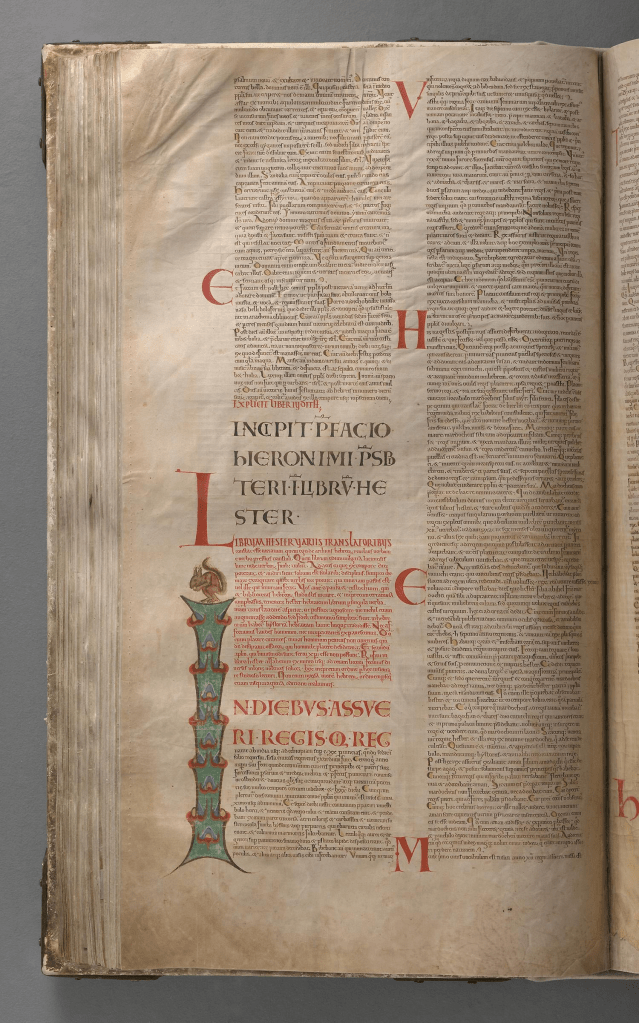

The manuscript itself is written primarily in Latin and contains many different texts and illustrations. In addition to the Bible, it includes works from authors such as Isidore of Seville, Flavius Josephus, and Constantine the African. In total, the book contains over 300 enormous pages. While history and scholarly works are included in the text, so too are references to magic. We’ll look more at the history of the book itself after first discussing what the text is most well-known for.

Towards the end of the book are two full-page illustrations: one depicts the Kingdom of Heaven, while the other shows something quite unusual and disturbing: a full portrait of the Devil. As such an illustration is quite out-of-place for most medieval manuscripts, this is a large part of why the Codex Gigas has remained so fascinating all these centuries later.

Why would the author of this text include such a portrait? As it so happens, there is a legend associated with the creation of this text. The story says that the author, a monk who broke his vows, was fated to be walled up alive as punishment. The desperate scribe promised to, in one night, create a manuscript that contained all human knowledge in exchange for being spared. As you can expect, the monk clearly realized that this task was beyond his capabilities, and so he ended up making a deal with the Devil. The scribe traded his soul for the Devil’s help in creating the text so that the monk would live. When all was said and done, the monk included a portrait of the Devil as thanks—or, perhaps, the Devil put it there himself.

This is certainly a fascinating story, and it makes the eerie portrait that much more frightening to behold. But what do we know about the book’s actual history?

According to the National Library of Sweden, where the Codex Gigas is held today, the first recorded owner of the text was a Benedictine monastery in Bohemia—though they say the monastery was likely too impoverished to have created the great book themselves, suggesting that it may have been written elsewhere. The book changed hands a few times after its creation. In 1594, the text was acquired by the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. He had a particular fascination in curiosities and the occult, so the Codex Gigas must’ve seemed quite desirable to Rudolf.

During the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), the manuscript was taken as war spoils by the Swedish Empire and placed in Stockholm Palace. Eventually, in 1878, the Codex Gigas was moved to the National Library of Sweden where it remains to this day.

How about the book’s author? According to the text itself, the man was known as Hermannus Heremitus, or “Herman the Recluse.” Based on the man’s name, even if the text was not actually written with the aid of the supernatural, it is possible that he may have secluded himself for many, many years in order to create this masterpiece.

The legend surrounding the “Devil’s Bible” has certainly helped to keep it within the scholarly and public conscience. Even so, we shouldn’t discount the immense accomplishment that the text represents. Setting aside ideas of the supernatural and demonic intervention, the fact that such a monolithic text existed as far back as the 13th century is amazing in itself. Many people likely believed the legend simply because the existence of the book at all was so impressive. Imagine writing a book so exemplary that people are convinced you must’ve sold your soul to have written it.

We should give some applause to Herman the Recluse for having created this impressive work in his time. Or, if you believe differently, maybe there was someone else, or something else, responsible…?

— r

Further reading:

If you visit the National Library of Sweden’s online section on the Codex Gigas, you can not only learn more about the manuscript, but even read the book yourself!