This week, we’re looking at a niche yet curious subject: the 1457 Genoese world map.

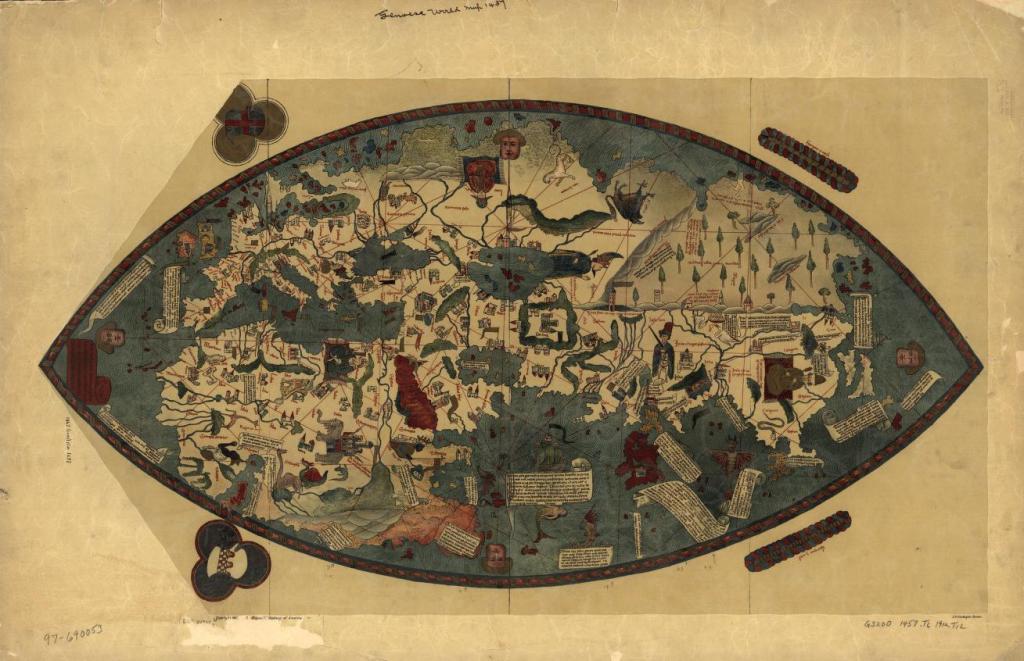

Let’s start with the basics: the author of this map is unknown. A trace of the flag of Genoa on the top-left corner provides some insight, but little else is known of its origin. The Library of Congress Geography and Maps Division has a facsimile that was replicated by the Hispanic Society of America in 1912. It is colored, crafted on a cloth material, and its dimensions are 47 x 81 centimeters (pictured below).

(Genoese World Map. New York: Hispanic Society of America, 1912. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/97690053/.)

Aside from the author of this map being unknown, the map itself is interesting due to its unique design at the time. Most maps that were created during the 15th century followed what was known as the T-O model. Maps that follow the T-O model are encapsulated within a circle, which represents the “O” with a “T” running through the center of the circle. Isidore of Seville said that the world was divided into three sides: Europe, Asia, and Africa, which were segmented by the “T” on these maps. Jerusalem was often placed in the direct center, and Paradise (or the Garden of Eden) would be depicted at the very top of the map. As you can see, the T-O model was heavily associated with religion. Faith was very important for medieval Europe, so it especially comes as a surprise that the Genoese world map was unique in this regard.

Another distinction is how the Genoese world map depicts the world in an oval shape rather than a circle. This was not unheard of in medieval Europe, however—in fact, the Earth itself was often described as an egg, or alternatively, an ark (religious influence, once again).

One possibility is that the map was intended more for display than for practical use. It is certainly artistic and colorful in its presentation. The illustrations of monsters and other fantastical creatures are charming but far from unique. Many historical maps included such illustrations both for flair and to indicate unexplored lands (called “terra incognita“). This cartographical trend is also where we get the phrase “Here be dragons,” which when written on maps, served the same purpose as adding these fantastical drawings.

We must applaud the work of this map, as even while relying on the accounts of Niccolò de’ Conti over the more popular Marco Polo, it provided more accurate proportions for world geography than most other maps of the time. Though we will never know for sure, this possibly could’ve been among the maps used by Christopher Columbus when his voyage changed cartographical depictions of the world forever. For us, however, the origins and authorship of this map will remain shrouded in mystery.

— r & c

Further reading:

Gerda Brunnlechner does an excellent job at breaking down the various elements of this map in her paper: “The so-called Genoese World Map of 1457: A Stepping Stone Towards Modern Cartography?“.